JFK, THE WISCONSIN PRIMARY, AND STRICT SARTORIAL SCRUTINY

So here I am in Covid day five (or four, depending on how you count). Completely self inflicted in a number of ways. First was a trip to NYC, riding train and subway blithely unmasked. Second, and more importantly, in the previous weeks I’d frequently bragged that my Serbian grandmother and Croatian grandfather had bequethed me a hardy peasant constitution that rendered me immune from viruses that felled the etiolated and effete, even if it did make me more forgiving of the occasional war crime. God heard me, and oh how He laughed and laughed!

(On the Balkan point, during the Yugoslavian unpleasantness in the Nineties I was frequently struck by how easily genocidal maniacs could have fit in at one of my family picnics. Later, when my in-laws returned from a trip to Croatia, I asked my niece whether all the men there looked like me. “Oh no,” she said. “They’re hot.”)

In any event I’ve been whiling away my convalescence with deep dives into the NYRB archives. This led me to a lot of Gore Vidal reviews which—Vidal having been a shirt-tail cousin of Jackie Kennedy—led to a movie that I watched last night on Max.

Drop everything.

Primary is now recognized as a revolutionary break in documentaries, a turning point in cinema verite—a genre I understand but can’t pronounce. Filmed in black and white with shaky hand-held cameras, it’s a record of the Hubert Humphrey-JFK faceoff in Wisconsin in April 1960 in the runup to the Democratic Convention. The movie was released the same year so I very much doubt the general election had taken place before its final edits. In addition to its depiction of a vastly different political landscape—the candidates ply the backroads in two-Rambler motorcades or take cabs to urban rallies—it reveals a great deal, perhaps inadvertently, perhaps not even noticeably at the time, about the candidiates themselves.

I was first struck that Hubert Horatio Humphrey was a much more natural retail politician than his opponent. He genuinely seemed to enjoy standing on dismal street corners in Toma and Manitowoc telling kids to give his campaign flyers to their moms and dads. And while his presentation to a bunch of guys in bib overalls about farm policy opens painfully, by the end he’s brought the audience to its feet.

But while JFK received something like celebrity treatment, thronged by autograph seekers at every stop, discomfort seemed to lurk behind the cocky grin. Was it a reluctance to seek the office just to please Papa when they all knew it should have gone to his martyred older brother? Natural diffidence? Or was it the back brace? Jackie, on the other hand, was pure political gold. At a rally in a Polish ward in Milwaukee she drove the crowd wild by speaking a single sentence in their parents’ language. In the reception line she offered each handshaker an identical entrancing smile and raised eyebrows, a delight-on-demand never equaled until Princess Kate.

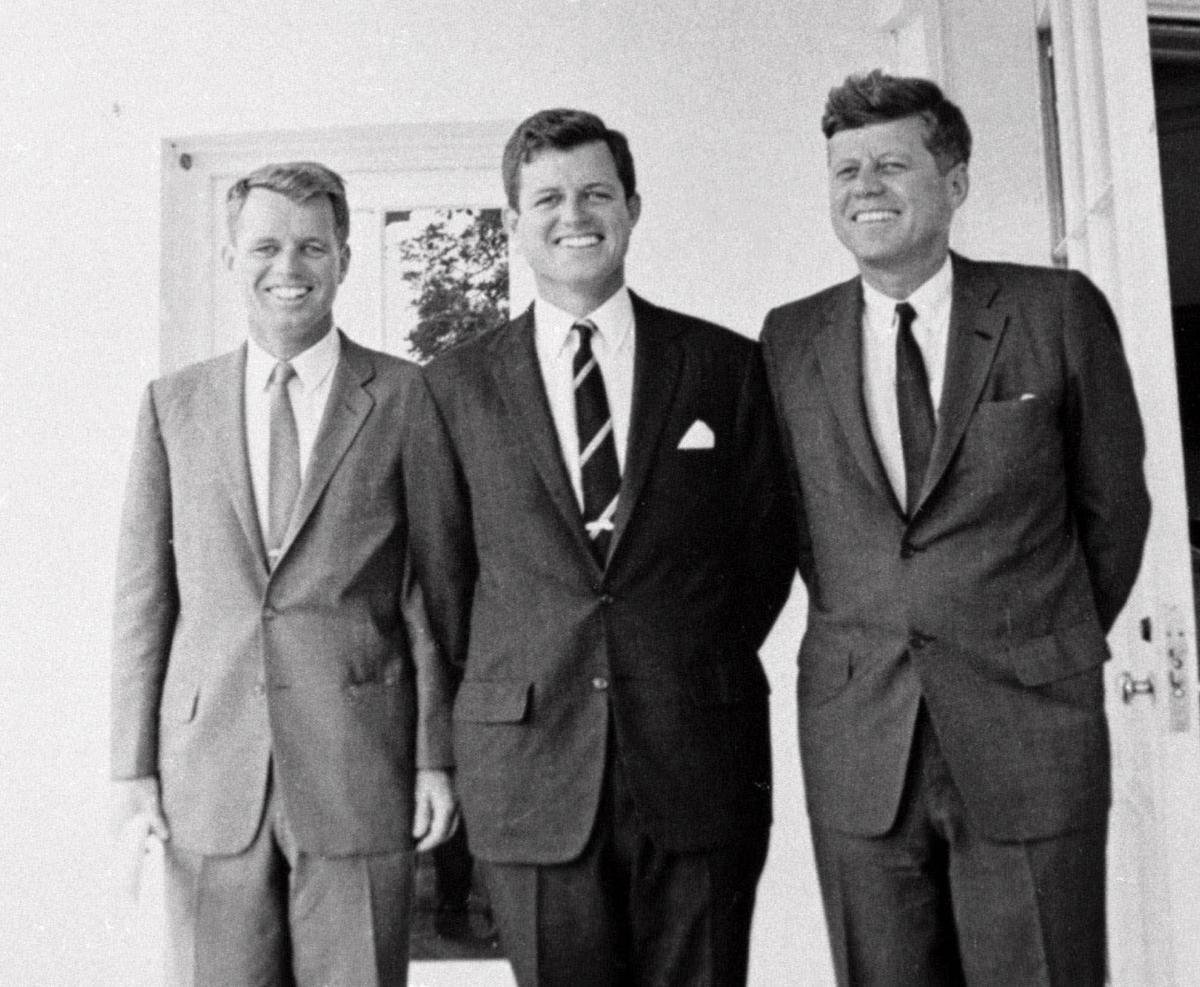

RFK briefly appeared and was surprisingly funny. I was struck then by just how skinny both those bastards were, a point not lost on the Wisconsin crowd—a Cheesehead matron was overheard whispering that Jack seemed to have lost weight again.

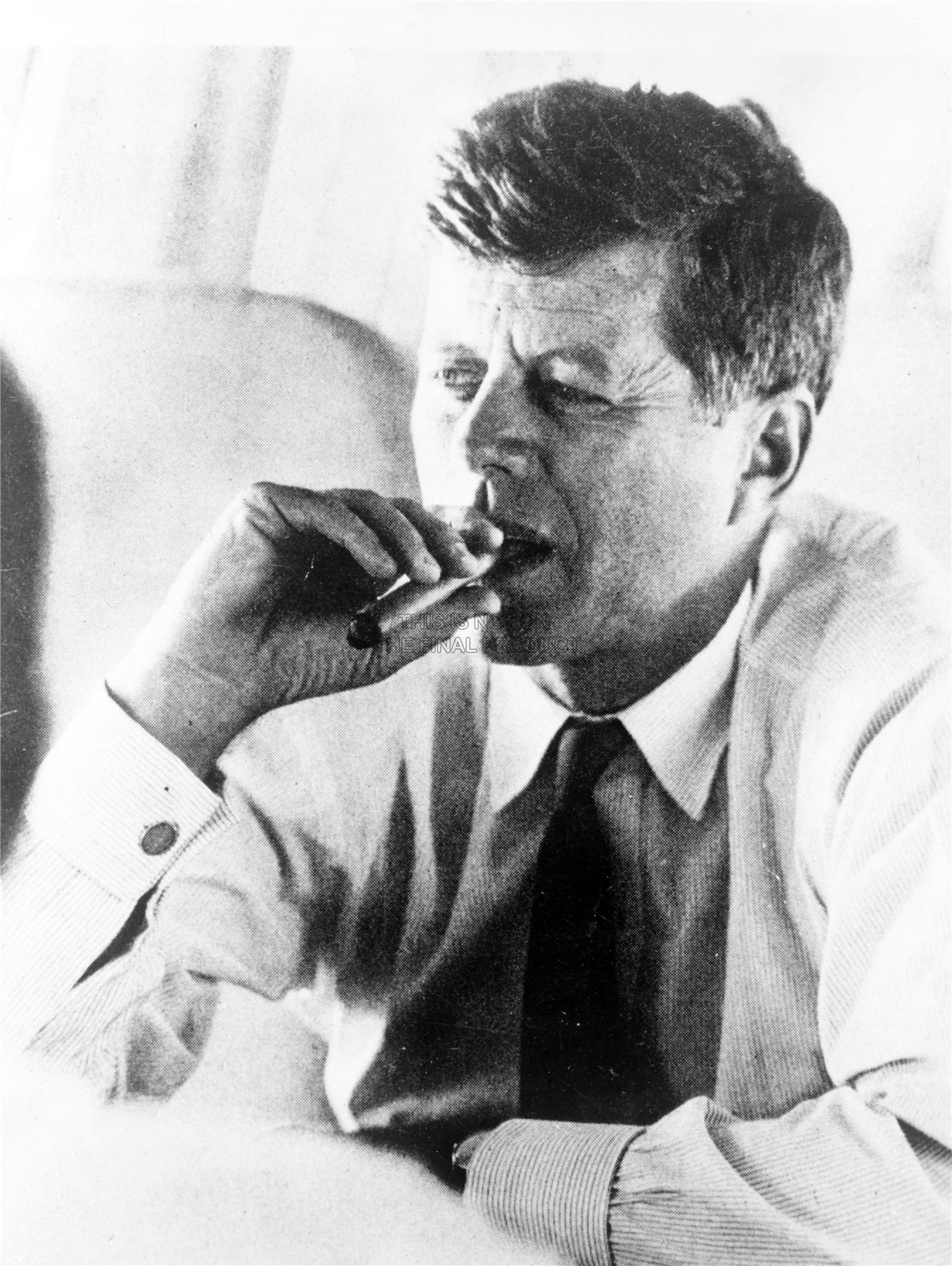

Some explanation for his slenderness may be found in his smoking habits. On election night he was filmed slamming down his cigars of choice, H.Upman Petit Coronas, until they were about to burn his lips. This was 1960, mind, so they were Cuban. I can tell you from personal experience that Cubans are not to be played with. A friend once correctly advised to smoke them sitting down and stand up slow. But I must concede that while nicotine is a powerful appetite suppressant, Kennedy’s ulcerative colitis and persistent malaria likely helped keep the pounds off too.

But the movie once again reminded me of a fashion rule that the otherwise elegant JFK seemed consistently, and inexplicably, to violate. From earliest boyhood—my first Communion suit in 1964–I had been told never to button the bottom button of a jacket or vest, one of the few rules I’ve followed scrupulously. Yet in every picture I’ve ever seen, this paragon of Ivy League style is completely, and improperly, fastened. But a few minutes of googling revealed that this was neither uncharacteristic slovenliness nor an Ill-conceived desire to set a trend, but rather, image control. He wore his back brace over his shirt and so needed to button the bottom to keep it from showing.

Somehow, that seems to be the point of the movie, however unintentional. JFK appears as player in a production orchestrated by others—or one other; though his father is never named, in his turn on the Milwaukee stage, Bobby references every member of the family but Joe, as though his power is such it can never be mentioned. Jackie’s European polish and effortless grace serve only to emphasize her husband’s OG Ivy League awkward charm. They stand in sharp contrast to Humphrey’s earnest Midwestern sincerity, delighted to take calls at an AM station with a hundred listeners. But most importantly, Primary is a stunningly authentic record of a political process whose candidates had not yet become the avatars of focus groups and media consultants entirely divorced from the electorate, where the Senator from Massachusetts could still catch a cab to the next event and the Senator from Minnesota could take a nap in the passenger seat of a Dodge with the lieutenant governor at the wheel.