MUSK CHANNELS LONG-DEAD TEEN SCI-FI AUTHOR

This is what a fourteen-year-old billionaire looks like

NOW THAT ELON’S BURROWED INTO MAGA LIKE RFK’S BRAINWORM, it’s time that we examine the thin-skinned neurodivergent Boer’s intellectual foundations. In several recent interviews he revealed a reading list of the books he considered to have been most influential in his development.

Unsurprisingly, among them is Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged (1957). It teaches a Hobbesian world in which only the extraordinary rise, that selfishness is the ultimate good, and altruism the ultimate vice. Her books have thus provided conceptual cover for the smugness, greed, and nihilism of generations of hard-right Republicans (looking at you, Paul Ryan!) Silicon Valley plutocrats, and all-around truculent dicks. Thus you’d think Musk would have committed it to memory long ago.

What’s striking, though, is that Musk has consistently placed in his top recommendations two books by a now-largely-forgotten American science fiction writer, Robert A Heinlein. Both appeared long before his birth. Stranger in a Strange Land came out in 1961; The Moon is a Harsh Mistress in 1966.

The writer

A little background: Heinlein was born in 1907, graduated Annapolis in 1929, and was invalided out of the Navy in 1935. To supplement his disability pension he turned to pulp magazines, writing short science fiction stories that soon gained him a following among the adolescent cellar dwellers able to cough up one thin dime for magazines with titles like Weird Tales and Astonishing Stories. (No disrespect intended—they are my people, as I will later show). War saw him working as a civilian at the Philadelphia Navy Yard alongside future luminaries Isaac Asimov and L. Sprague DeCamp.

Heinlein hanging with his boys. The author, right; Isaac Asimov center; L. Sprague de Camp left.

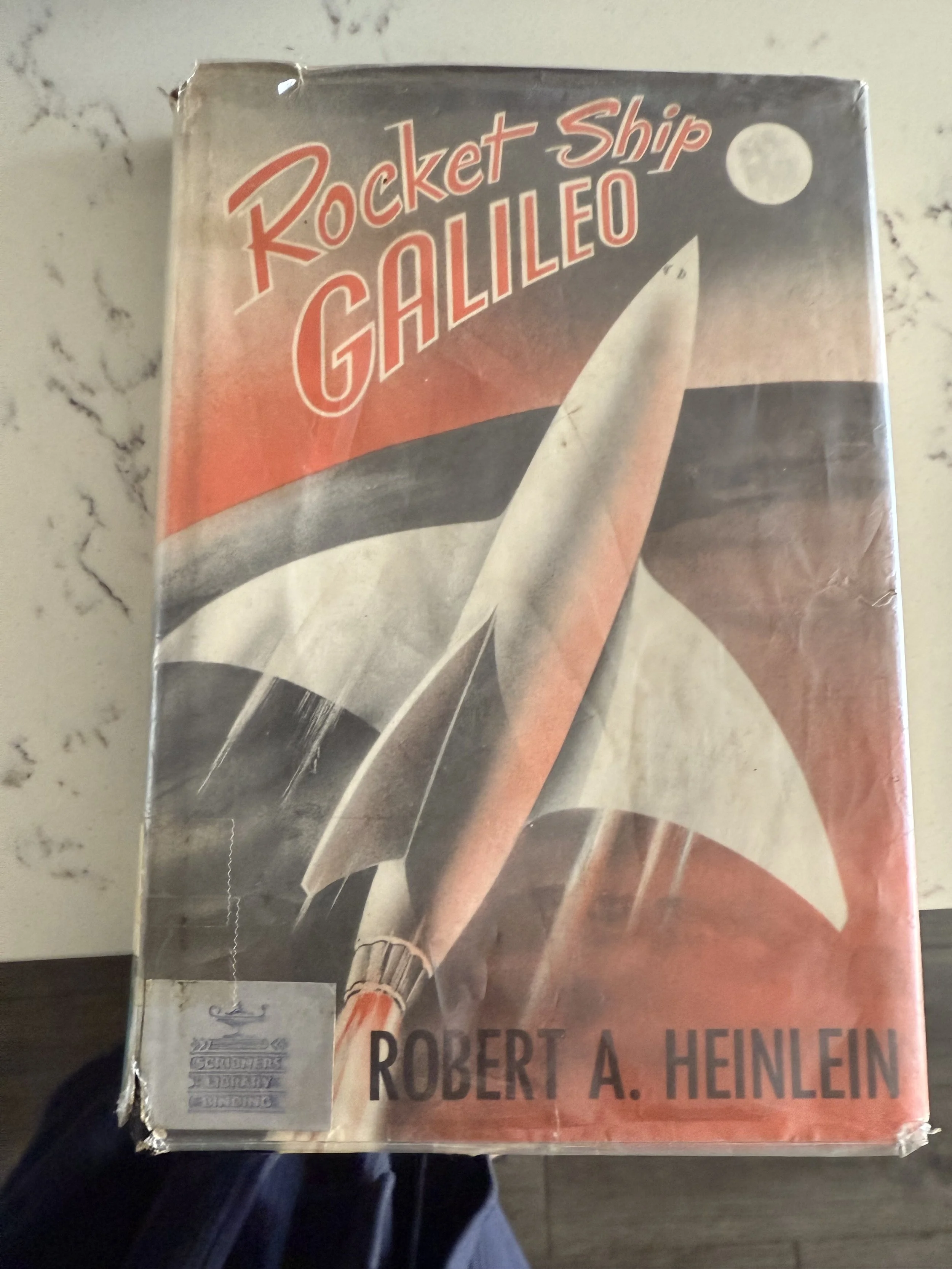

After the war, Heinlein launched a lucrative career of what was the then-ground-breaking genre of “juvenile” science fiction, cranking out a novel every autumn, just in time for Christmas. Their titles were succinctly zippy—Rocket Ship Galileo, Red Planet, Starman Jones, Farmer in the Sky, Tunnel in the Sky, Citizen of the Galaxy—and sure to attract their target demo. The themes were almost always the same—plucky teen overcomes stuffy stepparents (or stupid teachers, or poverty) to prevail in adventures on other worlds. The science was generally in keeping with the frontiers of the post-war era, and its failures of imagination were sometimes laughable—starships were steered by math-wiz navigators plotting their courses with slide rules as they smoked Luckies. While the books occasionally pitched Heinlein’s growing cranky-old-guy libertarianism, they largely stayed apolitical. The major deviation during this period was Starship Troopers, which took the alarming position that only military service—albeit in spacecraft in alien wars—is the proof of social commitment that entitles veterans, and only veterans, to vote or hold office. Though its movie adaptation varies from the book in many material ways, it visually communicates the kind of fascist future Heinlein dreamed up, presumably at the bar of the VFW.

The books

But none of these are Musk’s books. In 1961, Heinlein took a walk on the wild side with Stranger in a Strange Land. Twenty years after its predecessor vanished without a trace, an expedition from Earth returns to Mars and finds a sole survivor, conceived by a crew couple on the previous mission’s voyage and born on Mars. Raised by the Martians, he is now a grown man, Valentine Michael “Mike” Smith. Returned to Earth, his knowledge of mysterious Martian ways and hypothetical ownership of the whole planet—he’s human, and they’re just Martians, after all—makes him the subject of intense competition among politicans, plutocrats, and religious hucksters. He falls under the protection of cantankerous coot and genius-grade-lawyer-physican-writer Jubal Harshaw, whose kindly tutelage allows Smith to blossom into the prophet of Martian brotherhood, tranquility, telepathy, and superhuman self-control. (Oh, and free love and eating the dead). He is killed by an angry mob of American religious bigots but by this point Heinlein has also got us so far down the rabbithole of his accessible, individualized afterlife that it’s scarcely a tragic denouement. It may be this that led Musk to comment, “It went a little off the rails at the end.”

This book’s influence on Musk is self-evident. Something has to account for his irrational obsession with Mars as the vehicle of human survival. Naming this to his must-read list is not a clue deeply hidden. And of course, it’s not beyond reason to wonder whether Musk considers himself a stranger in a strange land, like Smith a visionary martyr arrived from the completely alien society of Arpatheid-era South Africa. And if there was any doubt, Stranger was the source of the word “Grok.” Heinlein invented it as the Martian term for a full, transcendent understanding of a person or concept. The phrase briefly made its way into 60’s hippie slang. But now it’s Musk’s name for his AI chatbot.

One wonders if he paid the Heinlein estate. One considers the pennywise Afrikaaner’s history and suspects not.

But it’s with The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress that we see Musk’s heart entire. It’s 2075. The Moon is a penal colony, initially populated by the convicts who built its underground cities and now their descendants as well as newly-arrived criminals. Governed from Earth, Luna’s main purpose is to grow grain for shipment to a starving Earth via giant electromagnetic rail guns.

Wait—what? Why in the name of the actual fuck would you send convicts to the Moon in the first place? How much would it cost to get them there and build their cities? And the grain? How much could three million people—Luna’s population—grow in subsurface tunnels, watered with melted ice mined by laser, nurtured by artificial light, fertilized by the ground-up bodies of dead colonists? Enough to make the slightest dent in Earth’s hunger? Enough to justify the staggering cost? Of course not.

But let’s leave that aside for the moment. The protagonist is a one-armed computer tech named Manny. Among his duties is servicing the colonial government’s supercomputer, Mike. (Short for Mycroft Holmes, a typically unfunny scifi pun arising from the name of IBM’s founder, Dr Watson.) Mike has recently become sentient—known only to Manny—and is exploring his newfound consciousness through bad jokes. (Picked the right genre, to be sure). In short order Manny is lured into a nascent Lunar Revolutionary movement by its mastermind, the Prof, and the firebrand hottie Wyoming Knott. (Yes—Wy Knott). With Manny comes Mike, literally the deus ex machina who coordinates the domestic phase of the revolution and ultimately the military—that is, using those electromagnetic rail guns to pound Earth into submission with million-ton chunks of lunar rock, pelting the planet like dinosaur-killer asteroids. (Pretty sure The Expanse stole this idea). For some reason, Earth’s Navy is incapable of using its lasers and nuclear weapons to breach subsurface cities that would be immediately uninhabitable once their atmospheres escaped. Earth gives up! The Moon is free! In 2076, the American Tricentennial, no less!

En route to this happy result, Heinlein has his characters—the Prof, generally—mouth his political philosophy, essentially hard-core free-market libertarianism. This is most evident in the new nation’s motto—TANSTAAFL! This, astonishingly, is not a Dutch word for a large table, but an acronym that might, in fact, have been ripped from the aforementioned Rand—There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch.

So far, this book would seem indistinguishable from the rest of Heinlein’s juveniles. What sets it apart is Heinlein’s response to the obvious problem raised by a convict colony comprising far more men than women. Not that in 1966 he suggested same-sex alternatives. Far from it. Instead most of the colonists engage in some variant of polyandry—two men married to one woman, or “serial marriages” that are essentially communes headed by a senior husband and senior wife, into which people marry over generations, brother husbands pairing up with sister wives as available. (Of course Wy Not marries into Manny’s group.) Pretty heady stuff, sixty years ago.

It’s worthy of note that as Heinlein got older, he got wilder—in I Will Fear No Evil, a dying white male billionaire’s brain is transplanted into the body of a nubile multiracial female employee. Hijinks ensue. And Time Enough for Love culminates in the immortal Lazarus Long—first introduced in one of the Fifties teen books—traveling in time and space to rural Missouri before World War I to fuck his own mother. Heinlein was born in rural Missouri before World War I. Ick.

But once more, it’s clear how this novel reverberated for Musk. First, of course, is the persistent notion that the human future lies elsewhere than Earth. AI appears in Mike. The lunar cities are interconnecting tunnels—hence, the Boring Company. Space travel, of course. So too the notion that government exists only to stifle enterprise. And you have to consider whether Musk’s Austin family compound, now under construction and intended to house many of his babymammas and offspring, has anything to do with the serial families that flourish on Heinlein’s Moon.

Heinlein, Elon, and Me

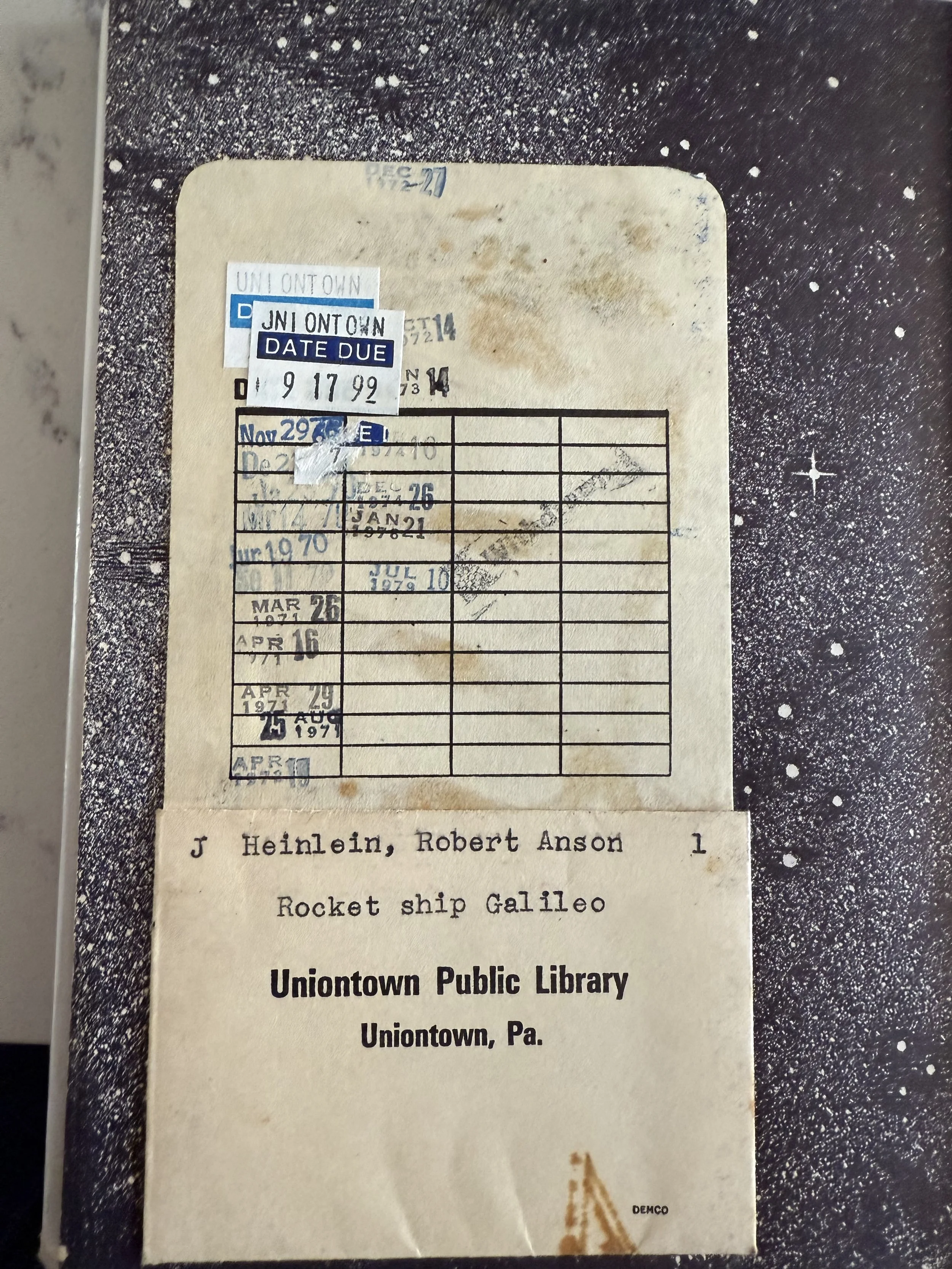

Left, the Uniontown Public Library’s copy of Rocket Ship Galileo, acquired at a book sale. Right, its checkout stamps. All those in the left column are mine.

Now here’s the thing: I didn’t have to do any research for this piece. By the time I was fourteen, I had memorized each and every one of Heinlein’s books, including the two under discussion. I didn’t have to Google anything.

And why not? Heinlein spoke to every bright, socially awkward boy in America. Even if girls ignored him and football players stuck I’M A FAG notes on his back in the cafeteria—a fate I barely avoided, to be clear, but witnessed many times—his intelligence and perseverance would lead him to a bigger world in which he was the hero, at last. I have no doubt that Heinlein instilled in millions of boys a buoyant optimism and faith in science. And I was one of them, a nerd to my bones’ very marrow, living for the day when I could board the Rocket Ship Galileo to explore strange new worlds and leave Uniontown Area Senior High in the rear scanners.

But we were boys. And if Heinlein and Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke got us over a rough patch of our adolescence, it was over, so were they. Sadly, to an adult they all verge on the unreadable—poorly written, with untenable premises, gaps in logic, preachy dialogue, and characters who could never be seen in a three-dimensional world. No grownup would ever consider any of these books formative or a significant influence on his fifty-year-old self.

With one notable exception.

As I mentioned at the outset, Musk was born long after these books were first published. How did he come across them as a kid in South Africa? Or was he already an adult in the US, making his first fortune in the gray area of a student visa? But in any event, how is it that he can say, decades and billions and billions of dollars later, that these juvenile fancies formed who he is today?

There is but one answer. Elon Musk, obsessed by rockets and big tits and simplistic authoritarian politics, is stuck in time. His development stopped as an adolescent.

He’s not the world’s richest person. He’s the world’s richest fourteen-year-old boy.