“EACH MAN KILLS THE THING HE LOVES”: Oscar Wilde’s Collateral Damage

Oscar Wilde is now viewed as the foremost martyr of Victorian homophobia. And justly so. But as Louis Bayard vividly shows, he didn’t go to the cross by himself. Not at all. His wife and sons went right up there with him.

Louis Bayard has long been the pre-eminent American author of historical fiction—and now that Hilary Mantel’s joined Thomas Cromwell (or more likely, gone someplace far better), perhaps the world’s. His earlier work blended genres—the thriller in Mr Timothy, in which a grown-up Tiny Tim breaks up a pedophile sex trafficking ring in 1870’s London, or The Pale Blue Eye, where Cadet Edgar Allan Poe helps solve a series of seemingly Satanic murders at West Point; the supernatural in Roosevelt’s Beast, whose Teddy and Kermit Roosevelt are plagued by a paranormal visitation during their near-disastrous trip down Uruguay’s River of Doubt. His most recent books, however, have been driven as much by character as plot. In Courting Mr Lincoln, he explores the fraught prairie bachelorhood of the sixteenth president, his affections divided between Mary Todd and his platonic (in fact, probably; in intent, not so much) roommate, Joshua Speed. Jackie and Me, published in 2022, also involves a three-way courtship. JFK’s lifelong closeted friend, Lem Billings, served as a go-between for him and Jackie before they became Camelot’s First Couple, duties that tested Lem’s loyalties to him while giving rise to an unexpected entanglement with her. Whatever Bayard’s focus, each book displays meticulous research, a deft command of its period, and a profound sympathy for its characters.

Wilde’s family: Wife Constance, sons Cyril and Vyvyan

No less is true of The Wildes. Bayard describes the book as a novel in five acts—fittingly, since Wilde was the most celebrated playwright of his time, rivalled only by Shaw. The first, longest act is set in the summer of 1892. Wilde has taken his wife Constance and their sons, Cyril and Vyvyan, off to a rented country house in rural Norfolk. With them are his mother, a slightly creepy Irish stage mom, as well as another couple, the Cliftons. Into this seeming idyll arrives Lord Alfred Douglas. At first Constance writes off Lord Alfred— “Bosie” to his pals—as just another of the etiolated esthetes who find their way to the Wildes’ doorstep. Not so. Soon it becomes apparent that something is going on between her middle-aged husband and their twenty-something guest, the nature of which is disclosed via strange sounds in the night and ultimately the discovery of an Elizabethan “priest-hole”—a hidden room—bearing evidence of carnal events. In a moving scene, Wilde comes clean and comes out to his devastated wife. Needless to say, the next few days at the summer place are awkward indeed.

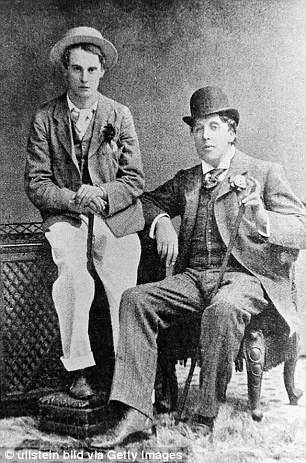

Oscar Wilde, right, and Lord Alfred Douglas

Bayard does not describe directly the fallout to Wilde himself. For the moment, suffice it to say that the forbidden relationship ruined Wilde, legally, personally, and professionally. Instead, the author concerns himself with the destruction wrought on his hapless family.

In the brief second act, we see Constance living in self-imposed exile in Italy five years later. Her health is deteriorating rapidly, thanks in part to the misdiagnoses and malpractices of a flirty local quack; the boys, isolated and ashamed, attend boarding schools under their mother’s name. In the third, in 1915, a grown-up Cyril is an infantry captain who’s volunteered to serve as a sniper in the trenches of World War I. Ten years later, on a rainy London night, his younger brother Vyvyan, now in his forties and the family’s sole survivor, encounters the critical actors from that long-ago week in the country. Particularly striking is Lord Alfred. In a scene reminiscent of the reunion between Charles Ryder and Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisted, the aging Bosie takes Vyvyan to a gay dive bar, where he’s known as a grifter and a sponge, to talk about their fathers and his own version of the events leading to the dissolution of the family.

In the fifth act, Bayard circles back to 1892 in Norfolk to imagine a happy ending. Or rather, an ending less catastrophically miserable. A clear-eyed Constance sees things for what they are and proposes a solution that keeps her family intact and her husband unruined. Not to give anything away, let’s just say some convenient fictions will be maintained and inconvenient truths ignored.

Here’s the thing: It might have worked. It would have worked. Only Oscar Wilde wouldn’t let it.

Let me hasten to add Bayard doesn’t say so. He treats Wilde with the same sympathy as all his characters. His only hint at Wilde’s besotted selfishness is when he shows him rejecting Constance’s openness to a family post-disaster family reunion to follow Bosie to some louche Continetal spa.

I noted above that Bayard does not directly describe the consequences of that summer week to Wilde. This clearly was a choice. If he had, it would have been impossible to maintain any sympathy for him. What happened is this.

Bosie didn’t get on with his father, the Marquess of Queensberry—yes, the boxing guy. Also one of the richest men in Scotland who sat in the House of Lords. When the Marquess got wind of the famous writer carrying on with his boy he didn’t take it kindly. One day he spun around to Wilde’s club and left his calling card with the porter. On it was scrawled, “For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite [sic].” Rather than laugh it off, Wilde let Bosie egg him into one of the most self-destructive acts since Brexit: He sued Queensberry for libel.

It didn’t go well for Wilde. Truth is a defense to defamation. When Queensberry’s lawyer revealed he had a parade of rent-boys, some under the very iffy Victorian age of consent, prepared to testify Wilde had paid them for sex, he had no choice but to withdraw the case. But that wasn’t the end. Sex between men—oddly, not between women—was illegal. Inexplicably, when he was tipped off that he was about to be arrested and urged to flee to France, Wilde remained passively in the Cadogan Hotel, sipping German wine and seltzer, just waiting for the policeman’s knock on the door.

His trial was a media sensation and a catastrophe. Wilde testified at length about the beauties of “The Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name.” The result was not in question. He got the maximum two-year sentence from a judge who openly regretted his inability to give him more. Broken by a Victorian prison, Wilde wandered the Continent for his two remaining years, living on a modest stipend his former wife generously provided. His plays, of course, disappeared from the stage.

But here’s the thing: it didn’t have to happen. The alternate history that Bayard presents in act five of The Wildes is no fantasy. It’s not as though the upper classes were unaware of the vagaries of sexuality—hell’s bells, they locked their boys up with other boys from before their voices cracked to military age, leaving them to couple like stoats in a sack. The Prime Minister at the time of Wilde’s trials, Lord Rosebery, was reputedly bisexual, and in a remarkable coincidence, was thought to have had a thing with one of Queensberry’s other sons—by Queensberry, at least. But Rosebery, unlike Wilde, kept it at least arguably on the down-low rather than flaunting it like a sunflower boutonniere. Had Wilde wanted to, with a few simple hypocrisies he could have had his cake and eaten it too.

This begs the question why he did not. It didn’t take genius to recognize that the Queensberry libel suit was likely to be the gunshot that started the avalanche. Yet he proceeded. Did he believe his verbal gymnastics would distract the jury from obvious facts? That his defense of Art would justify an exception on its behalf for its foremost practitioner, Oscar Wilde, Esq? Possibly he was that vain. The unfortunate thing about intelligence is that it provides so many compelling excuses for stupid acts. Or was he truly prepared to martyr himself for The Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name, as is suggested by his refusal to run in the face of imminent arrest?

Maybe ruin is what Wilde wanted. But his narcissism—and whatever his charms, his absorption with himself is undeniable—blinded him to its effects on those who loved him. Self-destruction rarely stops with the self. And however deep Wilde’s conflicts and deceits, he loved his family. He was a great father. His sons adored him. Yet as he wrote, after his release, of another criminal unfortunate, “Each man kills the thing he loves.” Or at least plays with that possibility when he sets out to destroy himself. It’s been remarked that suicide is the ultimate expression of selfishness because its perpetrator leaves all its consequences to his survivors and none to himself. Is any lesser self-harm different simply because the perpetrator suffers as well?

With his characteristic command of historical setting and empathy for the people inhabiting it, Bayard vividly shows us the consequences of Wilde’s fall from grace as they ripple across a generation of his blameless and beloved family. This is a book not to be missed.

.