EXTINCTION: WE HAVE IT COMING

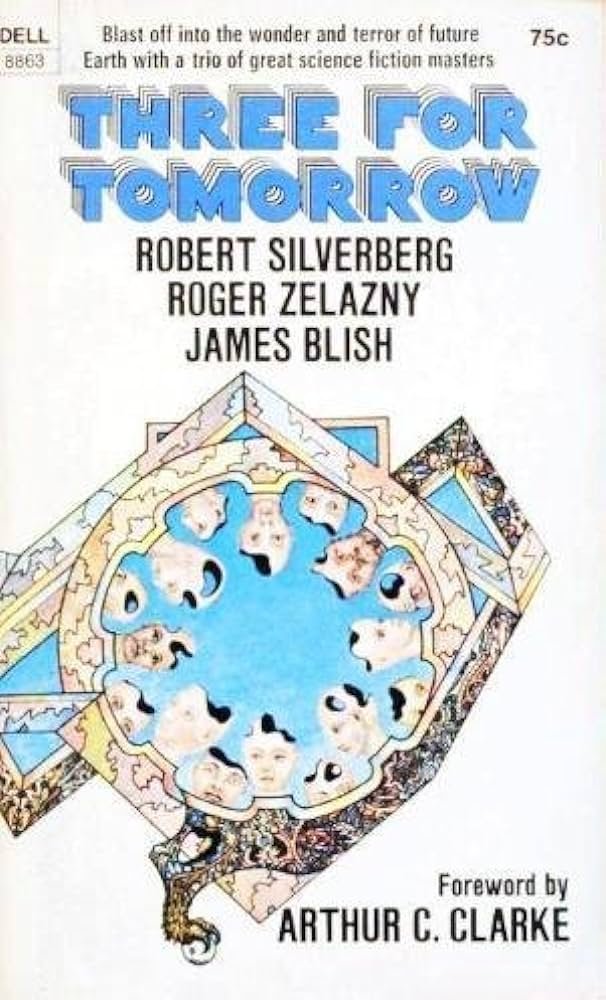

Left to right: James Blish; Three Tomorrows; postcard from 2040

“My God,” Alex said slowly. “And obviously it’s irreversible—we can’t take the carbon dioxide and other heavy gases out of the air. We’ve changed the climate, and that’s that. The ice is going to go right on melting. Faster and faster, in fact, as more energy’s released.”

——From “We All Die Naked”

In order to appreciate the self-inflicted nature of our present crisis consider the date those words were written:

1969

As gentlemen of a certain age will be, I’m periodically beset by nostalgia. For some guys it’s baseball cards; for others, muscle cars; others still, vintage sitcoms. As a teenage nerd once grown up and now rapidly aging, but a nerd still, I find myself returning to the science fiction of my youth to see how it’s held up, a process abetted by eBay. Some have not done so well: Robert Heinlein’s starships are navigated by sliderules worked through the smoke from outer-space cigarettes. Others perhaps better: in Arthur Clarke’s The City and the Stars, published in my birth year, our distant descendants, numbering in the hundreds of billions, upload their personalities into computer banks to be repeatedly reincarnated in endlessly variable combinations of contemporaries, a few million at a time.

But nobody ever hit the mark like James Blish. In what surely was intended to be a quick payday for all concerned, the aforementioned Clarke edited a three-novella collection for Dell called Three Tomorrows. The last piece is what concerns us. Its author had previously distinguished himself as the author of literate SF driven by high concept. In A Case of Conscience it was original sin; in the Cities in Flight tetralogy it was the social effects of antigravity as well as, ultimately, cosmology; in the After Such Knowledge trilogy it was black magic, eschatology, and the arms trade.

His contribution to Three Tomorrows is “We All Die Naked.” Its protagonist, the above-quoted Alex, is a Doctor of Sanitation and head of the incredibly powerful yet government-controlled garbagemen’s union. Incredibly powerful because in this near future the world is choking in its own waste—and drowning in globally-warmed rising seas. Manhattan, where the noontime temperature is never below eighty, is half submerged; downtown brokers paddle to work in kayaks, and at crowded intersections oar-fights break out in watery episodes of road rage. Grand Central has been turned into a cesspool into which toxic sludge is pumped. The Great Lakes are slowly filling with ground glass that is hoped will somehow dissolve within the next twenty thousand years. And of course disintegrating plastics have turned air and groundwater into a carcinogenic and mutagenic soup so that our Alex “had to think himself lucky that his nose wasn’t on upside down, or equipped with an extra nostril.”

This is in 1969.

Let’s consider what that means. James Blish was neither a visionary climate scientist nor an ecoterrorist. He wasn’t Rachel Carson or Paul Ehrlich. He was a working science fiction writer, intelligent and well read, and that’s it. But he knew enough to know what every other scientifically literate person of the late 60’s knew—burning fossil fuels was heating the planet. Describing the melting of the ice caps, he wrote this:

Carbon dioxide is not a poisonous gas, but it is indefatigably heat-conservative, as are all the other heavy molecules that had been smoked into the air. In particular, all these gases and vapors conserved solar heat, like the roof of a greenhouse.

——-p. 154

So if James Blish knew this, a lot of other people did too. Hell, I knew it; as a fourteen-year-old in a Pennsylvania coal town I was able to write a science report on global warming without plagiarizing too much from one source—because there were plenty. Yet throughout the ensuing fifty years, the coal and oil guys were able to convince a population eager to be fooled that the atmosphere was more than big enough to absorb all the CO2 their enormous single-occupant SUVs could crank out, just as the chemical industry persuaded us that the falling age of puberty and efflorescence of uncommon cancers had nothing to do with the weird new forever chemicals they were pumping into the water table.

When I first reread the story six months ago, after fifty fallow years, of course I was overwhelmed by the accuracy with which Blish had described what we’d have to call our nearly certain future and almost-present. But the story seemed to break down in what I thought to be a moment of unwarranted alarmism. It hinges on an even more catastrophic development—the injection of vast amounts of polluted water into deep aquifers had redistributed Earth’s mass sufficiently to change the angle of its axis of rotation. This in turn would trigger a new epoch of mountain-building vulcanism, and the only chance of survival was escape to an abandoned moon base.

Okay, I thought. You’ve gone too far. Not possible.

Then a few months later I read this.

Rampant Groundwater Pumping Has Changed the Tilt of Earth’s Axis

Yes, we busy little beavers have shifted enough mass around to change the rotational angle of a six billion trillion ton sphere that spins at a thousand miles an hour at the equator. What could go wrong, right?

The conclusion is inescapable that there is no impending catastrophe so obvious that we can’t ignore it. And nowhere is that point made more brutally than in the last days of James Blish. His day job, in the latter part of his career, was writing advertising copy for the Tobacco Institute.

In an irony he would have appreciated, if not enjoyed, his cause of death was lung cancer.