RECONQUISTA! The Mexican-Texan War of 2025

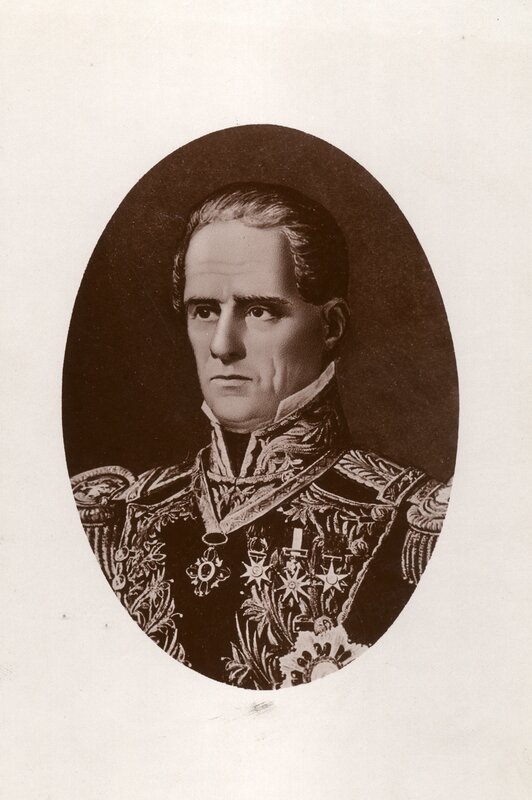

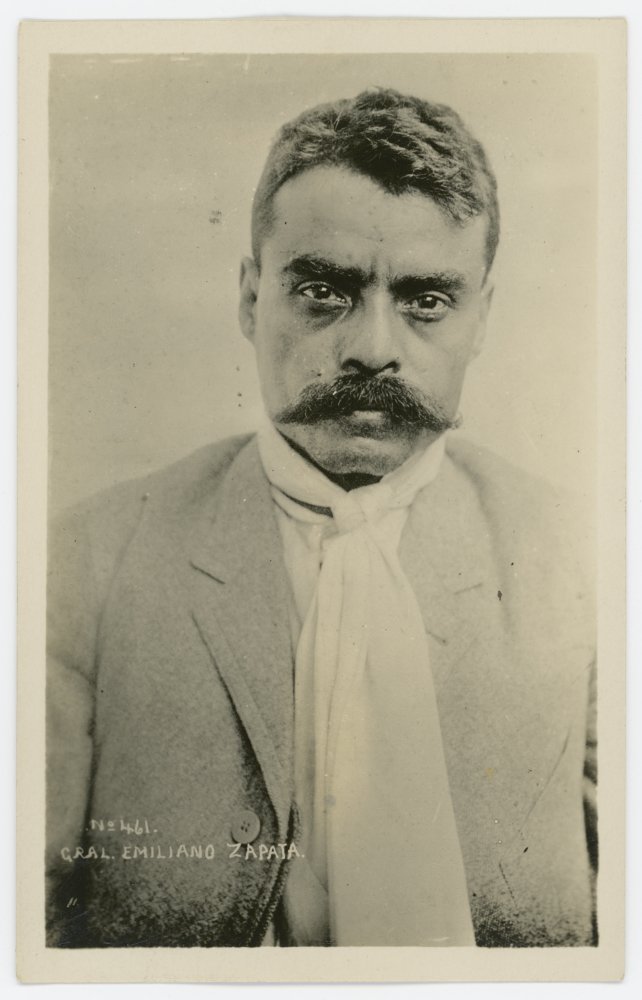

Houston, Santa Anna, Zapata, Abbott

(Among the most visible, if not the most profound, consequences of the political upheavals of the 2020’s was an extreme iteration of states’ rights gone terribly awry. Herewith selections from an account of those momentous days.)

Many Texans greeted the surprise victory of the Lone Star Republic Referendum with amazement and delight. Outside the major metropolitan centers and Austin’s academic districts, the streets were clogged with cowboy -booted and -hatted celebrants discharging their firearms into the air and, on not a few occasions, each other, unlucky accidents soon the subject of a general amnesty. But because secession’s triumph had defied the polls by so substantial a margin, few had considered the ramifications of abrupt nationhood, and assumed that life would go on much as before, but without the heavy hand of Federal “interference.”

They were rapidly disabused. The day after the Referendum results were announced, the state legislature appointed five Commissioners to negotiate the terms of the Texas Free Republic’s withdrawal from the Union. But it needn’t have bothered. Democratic factions in both chambers, advised by Constitutional scholars and hard-nosed tacticians, jockeyed through resolutions not only recognizing the secession, but giving it immediate effect. The Texas delegations attempted to block the measures, and would have given the Democrats’ narrow majority, but they found their own votes suspended after an immediate appeal to the respective Parliamentarians; shortly thereafter, their electronic Congressional passes stopped working. A panicked Republican Party shortly recognized the consequences of a forty-nine state Union in the upcoming presidential race and launched doomed legal efforts to redistribute Texas’ electoral votes among reliably red states. But with once-slender Democratic majorities suddenly enlarged by the expulsion of Texas’ legislators, the courts were soon stripped of jurisdiction over any effort to mitigate the consequences of departure.

Worse was soon to come. Texans considered themselves to be parties to an amicable national divorce, with joint custody over the benefits and resources they had always enjoyed. Millions of Texas seniors were the first to realize their mistake when their Social Security deposits failed to arrive. Any attempt to recover their former entitlement as birthright citizens had been pre-emptively blocked by legislation enabling the Fourteenth Amendment, ignored since the Civil War, that stripped citizenship from any American who willfully remained in a seceded state for more than ten days. There was, naturally, a flurry of attempted migration into neighboring states—the so-called Gray Hordes—swiftly shut down by a newly enhanced Border Patrol.

Of note, while many in Texas’ bordering states cheered on the secession and initially prepared to emulate it, imagining a grand southwest alliance, the economic consequences of exiting the United States soon persuaded them otherwise. While the Free Republic’s President-General—its former Governor—confidently announced that faith- and family-based charity would attend to the needs of the newly impoverished elderly, such was not the case. Soon famine stalked the nursing homes, and the disappearance of Medicare and Medicaid payments deprived the malnourished seniors of life-saving attention. Some retirement communities were compelled to convert their golf courses to makeshift cemeteries, and more than one reported instances of cannibalism. Naturally, given the number of elders who had migrated to Texas during its statehood days, this was an immediate political challenge for the new national government. It responded by tabling a temporary suspension of elections until the entitlement issue “got worked out.”

And of course that was just the beginning. The US military’s withdrawal, however haphazard and chaotic for the mother country, was an unmitigated disaster for the fledgling nation, suddenly deprived of a dozen bases and a hundred billion a year in desperately needed US dollars. While the Texas National Guard seized control of critical infrastructure, it could not provide the skilled workforce to operate it. Federal air traffic controllers, wary of payment in Lone Star Scrip, walked off the job, never to return; in any event, there was little for them to do, as neither US nor other carriers would send traffic to unregulated airports. The US Coast Guard and Corps of Engineers left the ports and levees to fend for themselves, resulting in catastrophic flooding and tens of thousands of deaths when, a month after the referendum, the first hurricane struck.

But the economic loss, however staggering, was nothing compared to what was to come. . . .

Recuerda el Alamo!

Many Texans considered their staggering hardships a fair price for what they had gained: Control over their own border. No sooner had the results of the Referendum been announced than newly “deputized” Rangers—generally vigilantes with home-made badges—flocked to the Rio Grande, where they formed so called “Wetback Patrols.” Initially they served only to reinforce the new Republic’s official law enforcement and paramilitary. These were savage enough. Though migration had slowed to a trickle as word of Texan independence traveled south, the actual Rangers were still eager to act on their new lethal-force authority, and often organized “turkey shoots,” sniping down whole families as they struggled to reach the riverbank.

Soon the Wetback Patrols, frustrated with their relegation to logistical support, took a more active role. Since the border itself was the prerogative of the Rangers, they took it on themselves to hunt down migrants who had made it into the Lone Star heartland. Driving “tacticals”—pickup trucks with swivel-mounted assault weapons converted to full automatic, made legal in one of the new Republic’s earliest acts—they terrorized Latin neighborhoods in every border town in “Beaner Runs.” Their technique was to confront suspect groups on the street, separate its members, and require each to recite the Pledge of Allegiance (Texas version) or the Lord’s Prayer in English. Those insufficiently fluent were disappeared—and often not very covertly; bodies were often found barely concealed in alleys, as a warning to others, with VAMOS placards pinned to their clothes.

These atrocities, of course, did not escape Mexico’s notice. As startled as most Texans by the Referendum’s success, its initial response was one of cautious friendship for “Nuestro Neuvo Vecino al Norte.” But as proof built up for the genocidal savagery of the Texas vigilantes, attitudes swiftly changed. (Many vigilantes’ were eager to share videos of Beaner Runs on social media.) Mexico was once overwhelmed by the relative population and wealth of the United States; but now, with Texas, the shoe was on the other foot.

Two incidents in rapid succession led to the outbreak of hostilities. First was the so-called Home Depot Massacre. Early one morning, several tacticals—their occupants obviously intoxicated, witnesses agreed—swept down on a Home Depot in the Austin suburb of Manor. Despite the secession and sealing of the border, it was still known to be friendly to day laborers, who gathered in its parking lot for landscaping or construction jobs.

What ensued was butchery. The “Deputies” drove in circles around the terrified workers, rodeo-style, emptying their weapons and sliding in fresh magazines until no one was left standing. “It was like the last scene of The Wild Bunch,” one horrified onlooker recalled. “Except the Mexicans didn’t have guns.”

South of the Rio Grande, revulsion and rage replaced cautious friendship. Streets in every city were shut down by demonstrations. The lives of American citizens were so clearly in danger that the US Ambassador took to national television to explain that the Massacre had taken place outside his country’s borders. A line from his speech—“Texas isn’t America, and Texans aren’t Americans!” soon appeared on posters and bumper stickers throughout Mexico.

Soon they were elsewhere as well. Within a day of the Massacre the Ambassador’s condemnation was echoed throughout Washington, and the President repeated it in an Oval Office address. A week later, many world capitals had been shut down by demonstrations calling for justice for the victims.

True to form, the Lone Star State defied world opinion. The President-General was initially cautious, remarking only that, “maybe the boys got a little out of hand.” But as pressure mounted, he took a harsher tack. “People from outside want to tell us how to live, let ‘em come here and tell us,” he said. “We got ropes and trees they can talk to us from.” UN sanctions against Texas oil exports followed almost immediately; the American failure to veto served only to exacerbate the breakaway state’s sense of aggrieved entitlement.

That, perhaps, is what led to the so-called Tijuana Incursion. Though the events preceding it may never be fully known, it is beyond doubt that the town erupted in rioting and general lawlessness in the immediate aftermath of the Massacre. Equally certain is that American and Texan citizens were among the victims of cartel kidnapers and random violence. Yet what followed was completely disproportionate: three hundred Texas Rangers in armored Humvees and an unknown number of vigilantes in tacticals charging across the International Bridge after midnight to “restore order.” When that day’s sun had set, the city was engulfed in flames and tens of thousands of Mexicans were dead.

Whether they acted under the President-General's orders remains uncertain; what is sure, however, is that the Mexican Government did not believe his increasingly strident denials. Obviously, though, elements within the administration had been preparing for just such a contingency. Within twenty-four hours, Mexico declared war on the Free Republic of Texas.

West Point military historian Lt. Col. William Bayard has described the reason for the outcome succinctly: “Texas believed its own bullshit.” No swarthy army could ever best steely-eyed frontiersmen and cowboys bearing the arms they’d stockpiled for a generation of Second Amendment absolutism. The cowardly and undisciplined horde pouring northward would break on the rock of Lone Star resolve.

Not so. First, while the Mexican Army was comparatively small for a nation so populous, it was still almost twenty times the size of the Texas National Guard—the former state’s only real military force. Second, if the Mexican Army was lightly armed—no armor to speak of and artillery scant—even its armored cars with 20-mm cannon were superior to the surplus APCs that were its opponent’s closest thing to tanks. And finally, however corrupt—and it was—the Mexican Army was on fire to avenge centuries of humiliation. Recuerdo el Alamo proved words to conjure with.

It’s surprising, in some respects, that the war lasted as long as it did. Flying columns crossed the bridges before the startled Texans thought to demolish them; special operators had already seized critical highway exchanges. In many respects their efforts were unnecessary, because the border—a majority-Chicano belt a hundred and fifty miles deep-- offered no resistance. Worse for the Texans, their initial, frantic efforts to organize a defense were frustrated by an active Hispanic fifth column. Thus within twenty-four hours Corpus Christi and San Antonio had fallen; in forty-eight, the government had relocated to Lubbock.

We can, perhaps, sympathize to some extent with the terminal desperation of the Free Republic. A transcript survives of a phone call between the Texan President-General and the US President, placed by the former in the rogue state’s last hours in a doomed plea for help.

P-G: Look, don’t make me beg. The greasers are coming down the chimneys, and we’re Americans too, goddammit.

P: Not any more.

P-G: (Frantic) Well Jesus Christ—just take us back! We’re sorry, okay? We’re sorry!

P: We did that once before. It didn’t work so well.

P-G: Hear that? Hear that? Small arms! We are completely fucked—oh Ken, hold me, please, just---

Call ends abruptly

Despite the intensity of feeling, the fall of the Texas Republic was marked by comparatively little bloodshed. It is perhaps for this reason that the United States immediately recognized the annexation and, in the Treaty of Bartlesville, relinquished most claims for Texas-American infrastructure Mexico had acquired. Though perhaps apocryphal, a conversation purported to have taken place between the chief Mexican and American envoys on the day of signing may explain the American attitude.

“The loss of so many of your former countrymen must be devastating,” said the Mexican.

“Nah,” the American replied. “They fucked around and found out.”