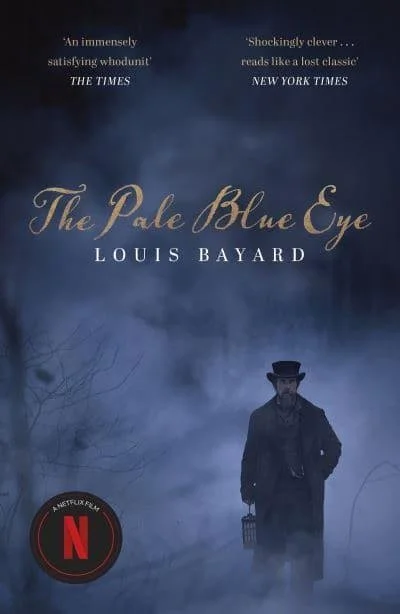

REVIEW: LOUIS BAYARD’S THE PALE BLUE EYE

I initially wrote the following in 2016, when I’d just finished the novel. Last night I saw the movie. You should too.

My father was convinced I'd make a fine army officer. This even though we'd not only met, but lived in the same house. It was his deepest ambition that I attend West Point. He decided that my reluctance would evaporate on contact with the realities of cadet life. So by the time I was seventeen I'd been to West Point twice. (He was wrong, by the way.)

A few weeks ago my muse and keeper, the pithy and enigmatic Mrs. H, interrupted a trip to Long Island with a sudden change to a destination she refused to disclose. As we paralleled the Hudson the territory grew oddly familiar. Suddenly I imagined myself in a '73 Newport filled with Chesterfield smoke. "Jesus," I said. "West Point?"

I have to say the place is much more interesting when you're not incontinent with terror at the prospect of actually attending it. And it did seem familiar, not only because I'd been there, but also was in the middle of Louis Bayard's masterful The Pale Blue Eye.

In 1830, the fledgling US Military Academy is rocked by the murder and mutilation of a cadet. To investigate the crime, its Commandant, Sylvanus Thayer--namesake of the strangely luxurious Hotel Thayer on Academy grounds, at which I had my first ever vichyssoise--retains the services of Gus Landor, a former New York constable recently retired to a nearby village. Landor moved to the Hudson for his health; ironically, it was his wife who immediately died, leaving him with a daughter whose later disappearance is mentioned only obliquely. As Landor insinuates himself into the Academy community, he acquires a Watson in the form of Cadet Edgar Allan Poe.

You heard me. Poe was at the Academy for a year before he got the shove. And as I'll say more about later, if Bayard is accurate--and I'm sure he is--Poe's lucky he didn't wind up a corpse himself.

As the investigation proceeds more cadets turn up dead, in circumstances more bizarre and fashions more grisly. The murders themselves, as well as evidence Landor uncovers, suggest the possibility of a ritual purpose. I'll say no more other than the plot is fast-paced, ingenious, and entirely credible, with a series of revelations in the last few pages that made me drop the cabernet.

But the plot, however arresting, is not the book's greatest strength. The characters will stay in your head for a very long time. The story is advanced by two narrators. One is Landor. In some ways he's a classic noir protagonist--hard-boiled, world-weary, but still driven by a sense of honor. Yet he's warmer and softer than a Phillip Marlowe or Travis McGee. He's the kind of guy I'd want to have a beer with--and Gus, he likes his liquor, hiding a jar of Monongahela whiskey in his hotel room. And there is something inexplicably paternal about his relationship with Poe.

I say "inexplicably" because Poe--the other narrator, in the form of a series of reports to Landor--does not make me want to have a beer with him. He makes me want to hit him in the face, hard and more than once. An affected, sneering narcissist, he is responsible for prose so purple it would make a cat barf. I actually road tested the Bayard version against the original on the shelf, and yeah, Bayard nailed it. Well, I already know how The Cask of Amontillado ends anyway.

But even more compelling than the characters are the evocations of place and time. Bayard unobtrusively captures the Hudson Valley's beauty, and does so when it's a still major throughway for a barely-industrial nation. As importantly he convincingly depicts it when it's thoroughly Dutch, without sounding like Washington Irving.

Louis Bayard has established himself as a master of historical fiction blended with other genres. I'm only sorry that I've now read all of it, and hope he'll write more soon.